After an absence exceeding two months, Falak Noor, purportedly kidnapped by a neighbor from her home in Sultanabad, District Gilgit, was presented before the Sessions Court on Thursday morning, where her statement was recorded before a judge under Section 164 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC).

Israruddin Israr, Regional Coordinator for the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), provided details regarding her court appearance and mentioned that her subsequent court date is scheduled for April 6 at the Chief Court.

Israr expressed hope that the Chief Court would implement significant measures on April 6, such as the formation of a medical board. “Our aspiration is for a comprehensive medical examination to assess her physical, mental, and sexual health, determining if she has endured any form of violence,” he stated. He further emphasized that the paramount welfare for any minor involves reunification with their parents, but should obstacles arise, alternative arrangements should be made for her care within a child protection unit.

Regrettably, Israr noted, “The GB Child Protection Unit is currently non-operational due to a lack of resources. The government must take immediate action to activate this facility. Currently, Falak Noor is housed in the women’s police station, temporarily designated as Darul Aman, a situation that is not sustainable for an extended period.”

Israr articulated that Noor necessitates psychosocial rehabilitation. Citing the Dua Zehra case as a legal precedent, he advocated for Noor’s court appearance post-therapy.

In a conversation, Falak Noor’s attorney, Wazir Shafi, disclosed that there was no prior notification about Noor’s court appearance. She was discreetly transported to the Sessions Court.

Shafi discovered this information upon leaving the courtroom on Thursday morning, at which point Falak Noor had already been presented before the Sessions Court.

“The legal representative of the opposing party had lodged a petition for Falak Noor’s testimonial to be recorded. However, we contested this request, arguing that under the Criminal Procedure Code, her statement could not be deemed lawful or admissible in court,” Shafi explained. “For her testimony to be accepted, she must be completely isolated from the defendant and his associates, relocated to a secure facility such as Darul Aman, and receive psychological counseling. Furthermore, her ‘B’ form, birth certificate, and all pertinent birth records, which have been submitted to the court, should undergo verification by a medical panel to accurately determine her age.”

Currently, there are two distinct legal proceedings underway. The first, in the Sessions Court, seeks the retrieval of the young woman and the apprehension of individuals named in the First Information Report (FIR), including 17-year-old Fareed and his father Azam Khan, accused of her abduction.

The second legal action involves a habeas corpus petition filed in the Gilgit Baltistan Chief Court. It is before this jurisdiction that Falak Noor is anticipated to make her next appearance on April 6.

A formal judgment states: “Given the Honorable Gilgit Baltistan Chief Court’s engagement with the case and the scheduling of the next hearing for April 6, 2024, it is ordered that Falak Noor be accommodated in Darul Aman/Women’s Police Station in Gilgit until said date, and thereafter be presented before the Honorable Gilgit Baltistan Chief Court.”

Furthermore, the court-mandated the Station House Officer (SHO) of the Women’s Police Station to prevent any unsanctioned private interactions with Noor during this interim.

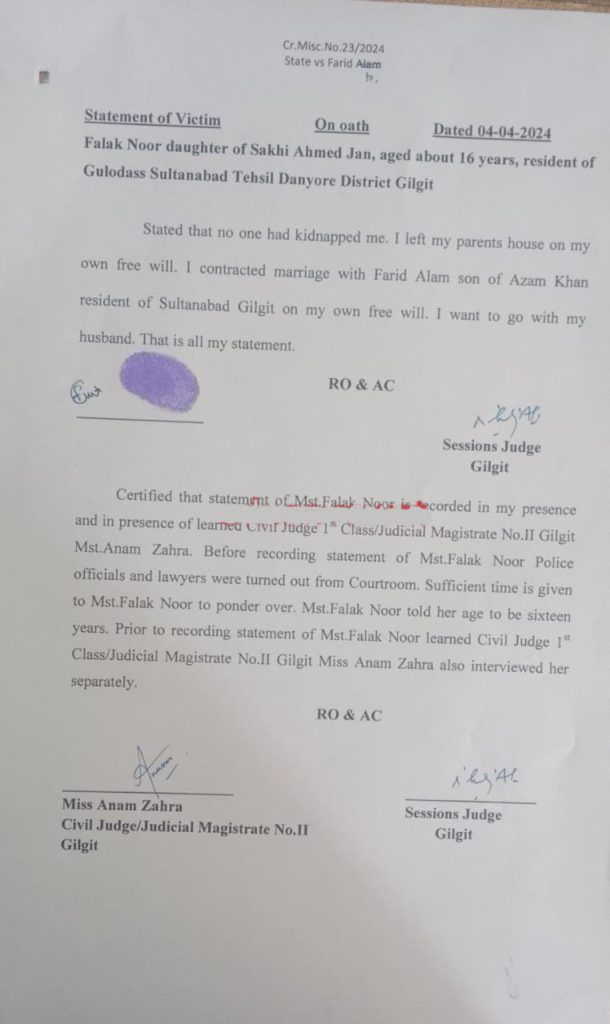

In her deposition to Judicial Magistrate Anum Zahra, Noor elucidated that she was not abducted but had left her familial home of her own accord. She revealed her marriage to Fareed Alam, a Sultanabad, Gilgit resident, affirming that it was a consensual union, and voiced her wish to reside with her husband.

“This situation transcends the bounds of mere child marriage, necessitating not only the arrest of the officiant and other participants but also constituting a clear instance of child trafficking,” Israr remarked. He noted that the marriage was solemnized in Havelian, where the girl declared herself to be 16 years old—a declaration that, even by the nation’s legal standards, categorizes her as a minor. “We were of the opinion that her testimony should not have been recorded in a closed session; however, we defer to the court’s judgment that this measure was taken to safeguard the child’s welfare.”

Israr, representing human rights advocates deeply engaged with this case, emphasized the necessity of holding all parties accountable for the manipulation of the girl’s age and the execution of the ‘marriage.’

The case’s legal team, assisting Noor’s father Sakhi Jan, has already submitted pertinent documentation to the court. These primary documents, aimed at ascertaining the girl’s age, include the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) certificate, the B Form, the birth certificate, and the school certificate. Collectively, these documents substantiate that the girl is approximately 12 years old.

According to statistics compiled by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), the nation witnessed a total of 70 child marriage incidents over the past two years. These incidents were geographically distributed as follows: two in Balochistan, four in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, eighteen in Punjab, and forty-six in Sindh.

A report issued by the Population Council and the United Nations Population Fund in November 2021 highlighted the prevalence of child marriage within the Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) region. It was found that approximately 26.78% of girls in GB are married before the age of 18, with 7% married before they turn 15. Israr shed light on a particularly distressing case last year in Diamer, where two young children, both in the first grade, were married. Additionally, instances of child sexual abuse have been reported in Baltistan and other regions. Diamer district recorded the highest incidence of early girl marriages, with 47% of girls married before the age of 18, followed by Shigar at 39.5% and Ghanche at 27.7%.

“The matter of the girl’s age presents a grave concern,” asserts Wazir Shafi, who is representing the case in the Sessions Court. “Given that official state documentation explicitly indicates the girl’s minor status, the question arises: how can her marriage be legally registered anywhere within the nation? If documents issued by NADRA are deemed inconsequential, then the rationale for the existence of such institutions must be reevaluated.”

“Indeed, Pakistan is not devoid of legislation about child marriage; the laws are unequivocally clear in deeming child marriage as a criminal offense, with various age thresholds established across different provinces,” a Gilgit-based activist remarked. “Moreover, the law criminalizes the harboring of minors and prescribes penalties for such offenses. Despite these provisions, we continue to witness an escalation in cases where children are coerced into marriages or elope to marry under pretenses, often without parental or familial consent.”