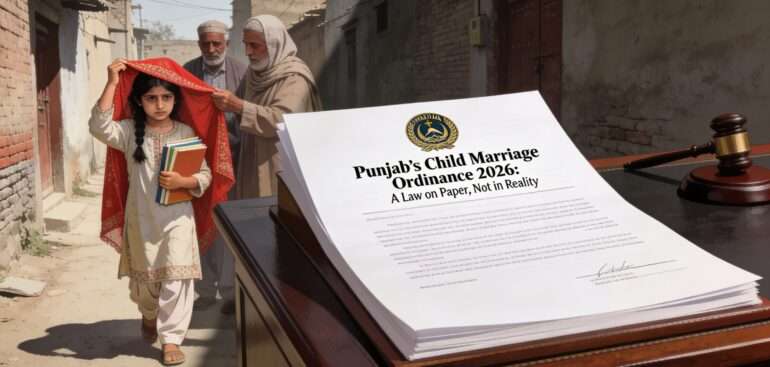

Punjab’s government has announced the Child Marriage Restraint Ordinance 2026, declaring that the minimum age of marriage is now 18 years for both boys and girls. Child marriage has also been made a non-bailable offence, with punishments of up to seven years in prison and fines reaching Rs1 million.

On paper, this appears to be progress. Headlines celebrate it, politicians congratulate themselves, and human rights statements are issued. But an uncomfortable question remains:

Who is this law really protecting?

For minority girls in Pakistan, this ordinance risks becoming nothing more than symbolic legislation—an impressive announcement with little real justice.

A Strong Law That Becomes Weak in Court

The ordinance replaces the outdated Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929, which shockingly allowed girls to marry at 16 while boys had to be 18. The new law removes this discrimination and introduces strict penalties:

- Marriage under 18 is now cognizable and non-bailable

- Nikah registrars can be jailed for registering underage marriages

- Adult men marrying minors face rigorous imprisonment

- Cohabitation with a minor is treated as child abuse

These provisions sound serious. But laws cannot protect victims when courts refuse to enforce them fairly—especially in cases involving minority girls.

Maria Shahbaz: A Case That Exposes the Truth

The heartbreaking case of Maria Shahbaz, a 13-year-old minority girl, reveals the reality behind the promises.

Maria was abducted, forcibly converted, and “married” to her kidnapper. Instead of returning the child to her parents, the federal court handed her custody to the very man who kidnapped her.

Her family presented a birth certificate proving she was only 13. The judges rejected it. Earlier findings declaring the marriage illegal were ignored. The girl’s so-called “consent” was accepted—as if a terrified child standing beside her abductor could truly speak freely.

In Pakistan’s justice system, a birth certificate becomes suspicious, while a kidnapper’s marriage claim becomes credible.

A Pattern Nobody Wants to Admit

Maria’s case is not an exception—it is part of a disturbing pattern.

Every year, an estimated 1,000 minority girls are victims of:

- Abduction

- Rape

- Forced conversion

- Forced marriage to older men

- Threats and lifelong captivity

Families run from police stations to courtrooms, only to be told their daughter has “accepted Islam” and is now a “wife.” Once religion enters the case, the law often becomes blind, silent, and conveniently helpless.

The Ordinance’s Greatest Failure: Ignoring Forced Conversion and Abduction

Punjab’s ordinance focuses on child marriage, but it fails to confront the real crisis faced by minority girls:

- Abduction

- Forced religious conversion

- Marriage under coercion

The moment a kidnapped girl is presented in court, the kidnapper suddenly becomes her “husband,” and the case transforms from kidnapping into a “family matter.”

The child is no longer treated as a victim—she becomes a legal complication.

Consent Under Fear Is Not Consent

Pakistani courts repeatedly accept “consent statements” from minor girls under extreme pressure.

What does consent mean when:

- The girl is surrounded by abductors

- Her family is absent

- She has been threatened or assaulted

- She fears returning home

- She is intimidated into silence

A child cannot consent to marriage. A child cannot consent to conversion. A child cannot consent while being held hostage. Calling this “free will” is not justice—it is cruelty disguised as legality.

Minority Girls Left in Darkness

Minority girls in Pakistan already face deep vulnerability due to:

- social discrimination

- harassment and exploitation

- blasphemy-related threats

- violence and forced captivity

- lack of state protection

When they are abducted, the state rarely rescues them. Police delay, courts hesitate, and the system collapses. Then politicians announce new ordinances and expect applause.

What Real Protection Requires

If Punjab truly wants to protect children—especially minority girls—symbolic laws are not enough.

Real reform must include:

- Criminalizing abduction and forced conversion clearly

- Treating forced marriage as aggravated kidnapping

- Prioritizing birth certificates and medical evidence in court

- Placing minor girls in safe shelters, not with abductors

- Punishing intimidation and threats

- Holding police and judges accountable for negligence

Until then, this ordinance remains a hollow announcement.

Conclusion: A Law Without Justice Is Just Ink

Punjab’s Child Marriage Restraint Ordinance 2026 is being celebrated as a milestone. But for minority families, it feels like another betrayal. Because a law that cannot save Maria Shahbaz cannot save anyone.

When courts return children to abductors, when consent is extracted through fear, and when minority voices are ignored, then no ordinance is a victory. It is only ink on paper. And for Pakistan’s minority daughters, paper does not stop predators. Justice does.