On a humid Tuesday evening, Sept. 2, the chants softened into hymns. After an unprecedented 17 days of fasting, prayers, and sleepless vigils, the Christians of Jaranwala folded their placards and did something they had not done since Aug. 16: they went home. They did not leave in defeat. They left on the strength of a federal assurance that justice—delayed for a year after the 2023 mob attacks—would finally move from speeches to action.

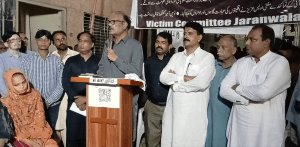

“This is the first time in our history that Christians have staged such a prolonged protest for their rights,” said Lala Robin Daniel, convener of the Victims Committee of Jaranwala. Within a 10-kilometer radius—streets, graveyards, and churches—the community refused silence. For years, they had endured more than a dozen mob assaults. This time, they answered with presence: vigils in sanctuaries, prayers among graves, banners in alleyways that smelled of ash and monsoon.

The sit-in began on Aug. 16 at Christian Colony, the anniversary of the day a frenzied crowd ransacked more than 25 church buildings and 85 homes after two Christian brothers were accused of blasphemy. From the first hour, women stood at the center—fasting, organizing, speaking, shepherding the elderly and the young to safe corners when tempers flared. Many left daily chores and wage work to ensure their voices were heard. When the government finally agreed to talk, three women joined the negotiation team so those carrying the heaviest burdens could name them, plainly and without mediation.

“Talk to us directly,” Daniel urged officials and elites who prefer hotel ballrooms to narrow lanes. For months, self-appointed advocates staged photo-ops and issued statements, yet seldom entered victims’ homes to verify compensation or case updates. When federal representatives finally met the Jaranwala delegation in Faisalabad, they did not pressure them to disperse; they promised results. With monsoon floods rising and a written assurance in hand, the committee suspended the sit-in, coupling restraint with a clear warning that if nothing changes, they will return in greater numbers.

The record to date should shame a nation. After nationwide condemnation, more than 300 people were arrested for the riots, yet convictions remain at zero. On June 4, an anti-terrorism court in Faisalabad acquitted 10 named suspects linked to a burned church and a ransacked home. Of 5,213 suspects initially apprehended, only 380 were actually arrested; 4,833 remained at large a year later. Of those detained, 228 secured bail, and 77 had charges dropped. Numbers, yes—but behind each one is a family counting losses that do not fit into ledgers or case files.

Blasphemy accusations in Pakistan can carry the death penalty, but it is often the rumor that executes the sentence. A whisper becomes a crowd; a crowd, a fire. The two brothers at the center of Jaranwala’s nightmare were later acquitted when a court found they had been framed by another Christian after a personal dispute. Acquittals do not rebuild sanctuaries or return sleep to those who learned that a neighbor’s shout can erase a lifetime of coexistence. Justice late is not justice restored; it is memory kept raw.

What would justice look like now? It would start with credible investigations that meet the burden of proof, not the theater of mass arrests. It would prosecute those who incite crowds as well as those who strike the first blow. It would deliver transparent compensation that reaches every family, and audited reconstruction funds approved by the community itself. It would guarantee protection so the next rumor does not become the next arson. And it would reform procedures around blasphemy allegations to prevent weaponization and collective punishment.

The Jaranwala sit-in has already changed the civic landscape. Protest in the streets is familiar; protest in graveyards is a theology of memory, a refusal to forget. Protest in churches resacralizes space, insisting a sanctuary can be both a house of prayer and a house of rights. Minorities are never only themselves; they measure the republic’s promise to all. If those at the margins can win redress, the many can believe the law is not a stranger they meet only on days of trouble.

Officials have given their word; the protesters have given theirs. Between these vows lies the test of the state. Seventeen days without silence have ended, but the echo endures—an insistence that the next government bulletin be written in charges filed, trials concluded, reparations paid, and guarantees honored. Until then, the community’s parting prayer stands like a banner over the colony: We will not rest until we get justice.